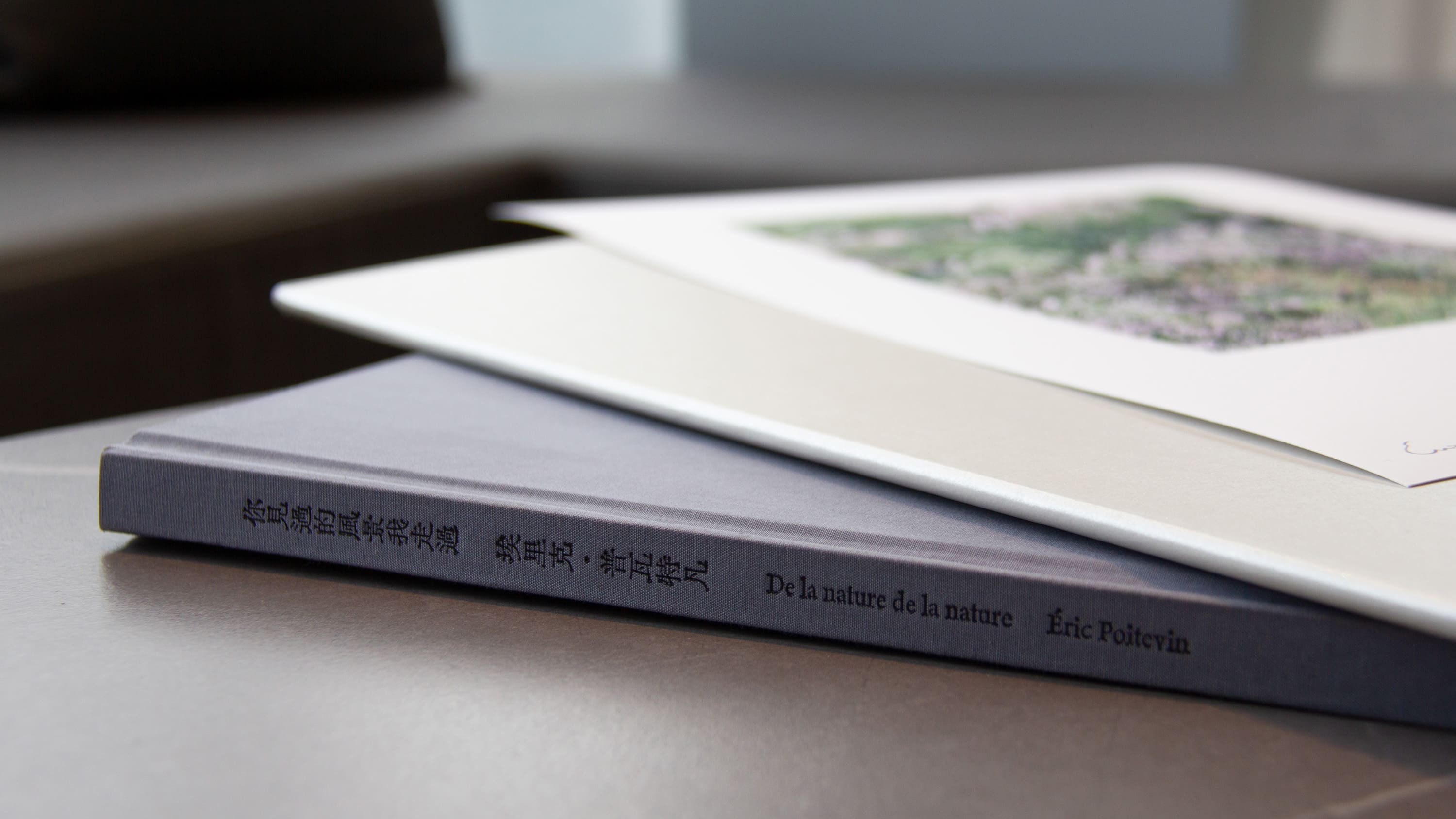

As Time

Time Is the Measure of All Things

HUANG Chien-Hua, Ph.D. in Art Creation and Theory, Tainan National University of the Arts

“Time is the thing. Time is the essential piece of interpretation. You cannot start without me. See, I start the clock. Now, my left hand shapes, but my right hand—the second hand—marks time and moves it forward. However, unlike a clock, sometimes my second hand stops, which means time stops. Now, the illusion is that, like you, I’m responding to the orchestra in real time, making the decision about the right moment to restart the thing, or reset it, or throw time out the window altogether. The reality is that, right from the very beginning, I know precisely what time it is, and the exact moment that you and I will arrive at our destination together.”

— TÁR (Todd Field, Director)

The first time I stood in front of Éric Poitevin’s work, his photography immediately called to mind the opening scene of the film TÁR, which features the reflection on “time” cited above from an interview between the protagonist, Lydia Tár, and Adam Gopnik, a staff writer for The New Yorker. That interview offers clues to possible ways of approaching Poitevin’s work. If photography is likened to conducting, then at the moment the shutter is released, a fundamental question emerges: What kind of vision is the artist ultimately pursuing?

The Naked Eye

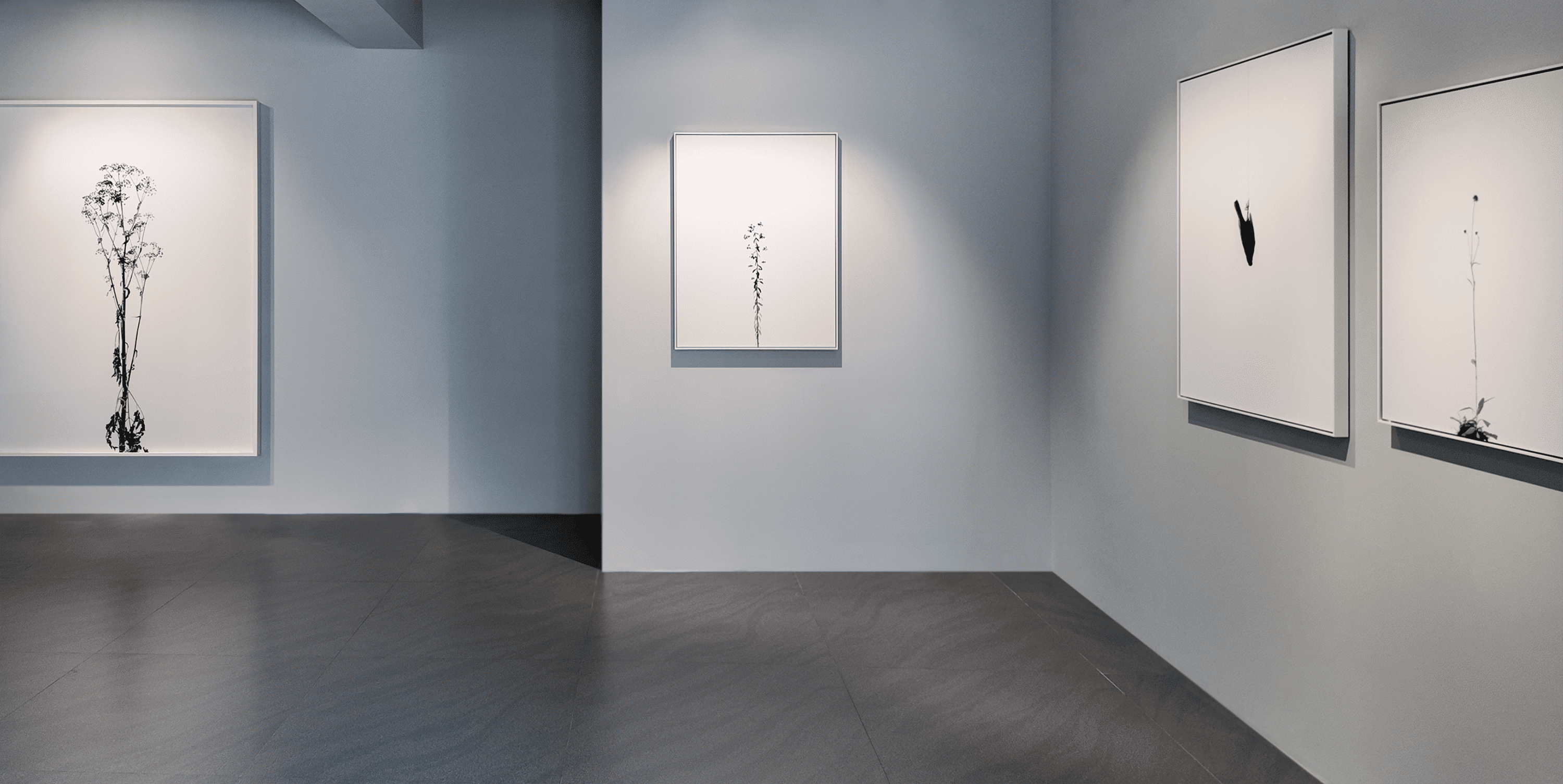

Intuitively, the solitary plants presented by Poitevin bring us back to the purity of viewing. Admittedly, this is not an easy task in the digital age. These works naturally evoke the seminal Fern series [1] in the history of photography, which offered its contemporaries two key insights: first, beneath what is visible to the naked eye, photography reveals details far beyond existing frameworks of knowledge; second, it points out the subtle and endless layers within the image itself. Since then, viewers have become increasingly preoccupied with the minute details of images. However, as we move further into the digital age, another reality becomes ever more apparent—details are often reduced to grid-like pixels, gradually diluting the possibilities of exploration and perception within a highly technical viewing experience.

Nevertheless, within the expansive field of view and the white blankness of Poitevin’s studio space, light blends naturally with the forms of the plants. The depth of field draws out subtle intervals of air and movement, while the growth of the plants harmonizes perfectly with this blankness. This “blankness” is not emptiness but a profound silence. It does not point to any tangible setting, yet opens a spacious and secure breathing space for these lives. The “light” here is not meant to illuminate; rather, it gently “supports” the plants, becoming a subtle, inward revealing force that both presents them and preserves their inherent modesty.

Untitled|Giclee|128 × 100 cm. (Image) 130 × 102 × 4 cm. (Frame)|2017|Ed.5. Untitled|Giclee|110 × 88 cm. (Image) 112 × 90 × 4 cm. (Frame)|2018|Ed.5. Untitled|Giclee|110 × 88 cm. (Image) 112 × 90 × 4 cm. (Frame)|2014|Ed.5.

In this context, the image reveals a quality between specimen-like presentation and still life, with a painterly stillness. The plants seem suspended in a nearly weightless realm, and it is this sense of ethereal lightness that imparts a fresh and clear texture to each of them. At the same time, the focus of vision creates a gentle rhythm of observation, allowing viewers to engage with the objects without approaching them too closely. In this way, viewers can experience the scene with focused and pure attention, as if brought back to a classical and beautiful era.

Resurrection

For a long time, discourses on the subject-object relationship in photography have often addressed the constraints imposed by the apparatus or the condition of being trapped within established habitual contexts. Jean Baudrillard once proposed a thought-provoking concept, [2] suggesting that the subject may only serve as an instrument through which the object expresses itself, functioning much as light, the lens, or the shutter would. Undoubtedly, this concept readjusts the distribution of power between the subject and the object in the process of photography, emphasizing the object’s active agency yet diminishing the subject’s position of control. No longer merely the projection of the subject’s desire, the object may instead summon and shape the act of viewing, even possessing the capacity to inspire the subject. In the history of photography, this viewpoint represents both a reaction against the belief in “the subject’s control” and an opening toward possibilities for viewing centered on the object. However, it is not difficult to grasp this idea. Most people with photographic experience recognize that many of the most moving moments are unplanned and impossible to foresee.

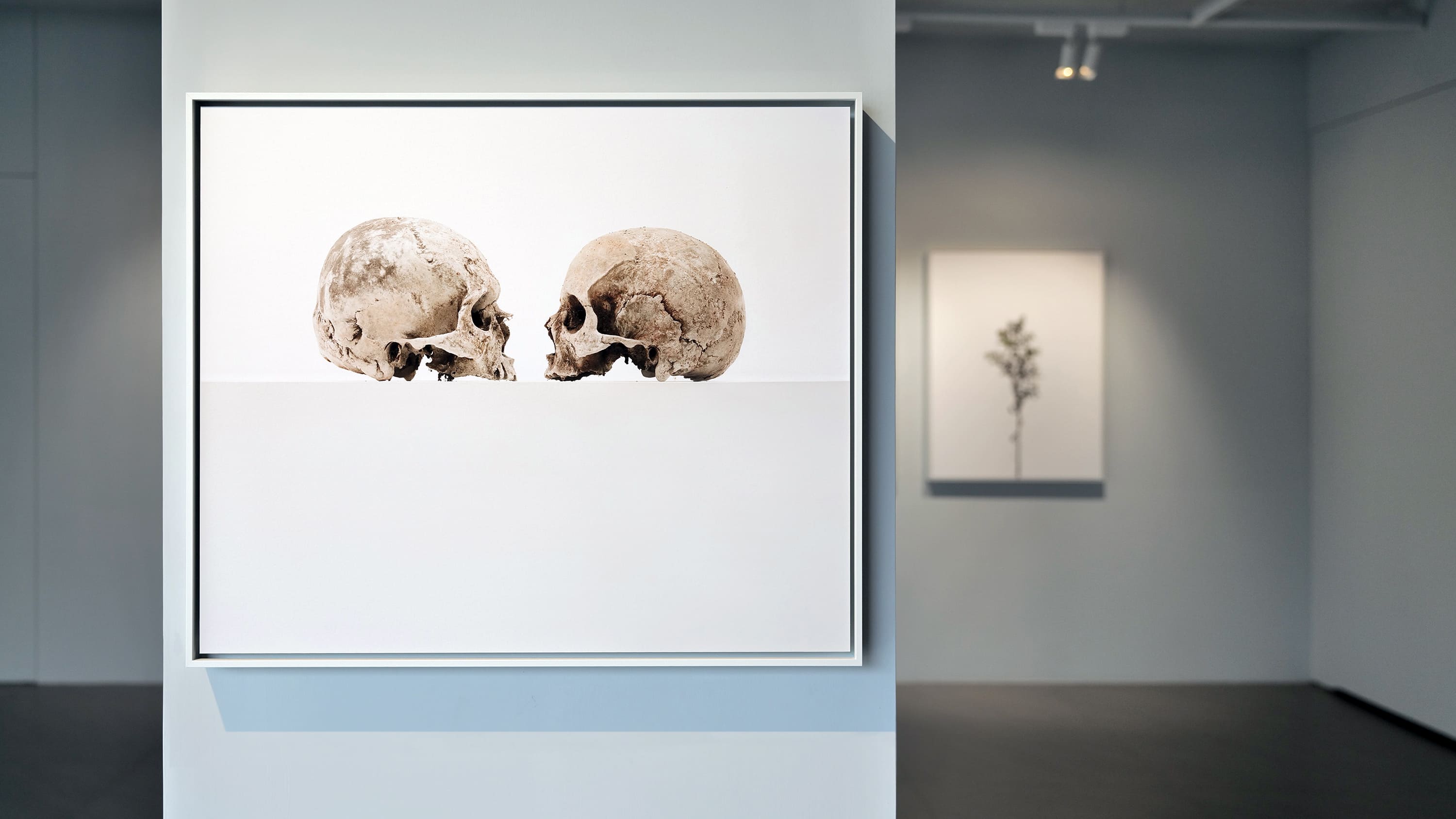

In an interview with Jean-Charles Vergne, Poitevin recalled a peculiar and unforgettable experience: “When I was ready to photograph these suspended birds, with everything in place, the first thing I did was to thaw one I had previously preserved—the barn owl waiting for me. I was deeply captivated by the process of watching it slowly transform from a stiff, lifeless block of ice back into a supple body, with its muscles and joints gradually restored. During those few hours, I almost thought I was witnessing a resurrection…” [3] It is easy to understand why, in that moment, as the barn owl physically thawed and warmed, its feathers loosened and softened, trembling faintly. It seemed to awaken again, as if its body had begun to remember its original contours and posture, drawing the photographer back toward it. The so-called “resurrection” (résurrection) here is neither a return to original life nor the finality of death, but rather the passage from death back toward life. What Poitevin seeks to capture is precisely this moment that defies traditional photographic ontology. He hopes the animals in his images retain a certain softness, and the key lies in their eyes, nose, and mouth preserving a slight moist sheen. He notes: “It’s a kind of illusion, an in-between state, that I wanted to photograph.” [4]

Untitled|Giclee|110 × 88 cm. (Image) 112 × 90 × 4 cm. (Frame)|2012|Ed.5. Untitled|Giclee|80 × 63 cm. (Image) 82 × 65 × 4 cm. (Frame)|2015|Ed.5.

Balance

Poitevin’s forest imagery, shot in natural light, features mist, damp moss, and dappled light and shadow filtering through branches and foliage, while containing no distinct figures, animals, or dramatic events. If such imagery possesses a “punctum”—“that accident which pricks me” [5] —it may lie in how these utterly ordinary details generate, from point to plane, a form of “penetration”: a sudden flash of sensibility that pierces perception by chance. Without aspiring to grandeur, these forests embody an inner order in the fleeting instants when light falls across the scene. Though the images may appear chaotic and overgrown, they consistently maintain a subtle yet steady tension. This is precisely an extension of the punctum—the piercing of that moment is never excessive, but instead tempered by the photographer’s composure and poise, creating a balance between calmness and emotion.

Thus, within this visual atmosphere, viewers may enter the forest—a place “where poetically man dwells.” [1] Here, “poetically” does not invoke Romantic sentimentality, but an openness that allows Being to disclose itself. Poitevin’s long hours of walking and waiting in the forest constitute precisely this practice of “letting things show themselves.” He does not seek to impose photography upon nature; rather, he dwells with the forest amid the shifting interplay of light, humidity, history, memory, and time. Such dwelling forms a balanced mode of inhabitation, in which the photographer is neither a detached observer nor a sentimental escapist. Instead, he adopts an attitude of “listening to Being,” allowing the world to appear in its own rhythm. In doing so, the forest becomes not only a representation of nature, but also a field of vision.

It is through this understanding that “balance” gradually transforms from merely visual stability into an attitude of Being—a way of maintaining openness and self-discipline between viewing and being viewed. While “punctum” emphasizes the force of penetration, “dwelling” stresses a sustained inhabitation; Poitevin’s photography occupies the space between the two. His forest imagery simultaneously captures the sudden spark of emotion and the quiet continuity of stillness, guiding viewers to attune perception and reflection within the imagery, as well as to rediscover the weight of Being in silence. Hence, viewers are neither overwhelmed by emotion nor able to withdraw entirely, but instead find a breathing rhythm between the sensible and the rational, learning once again how to “dwell within the imagery.”

One scene in the film shown in the exhibition is particularly impressive: Poitevin stares intently at the viewfinder as he photographs, his body visibly twisting and adjusting. At one point, he leans to the left, bending his neck at nearly a ninety-degree angle. He watches the screen in a posture that is unnatural, slightly eerie yet utterly captivating. This posture seems less about composition and more about his attempt to misalign his body from time and the world, allowing his gaze to be recalibrated in an instant.

It is from this bent body that an axis subtly emerges—one that threads through plants, animals, and forests. Though seemingly dispersed, they all converge upon a single core: stillness, life, and balance. In Poitevin’s photography, time does not serve as a background condition, but the very substance of creation. The purity of plants, the mediating force of life, and the interwoven pulse of woods all seem suspended, stretched, and gently set down by photography, making us aware that phenomena are never still, but rather different configurations of time. Through that bent body, we see the primordial question of photography: the photographer’s adjustment of himself to respond to the rhythm of things—a way of “placing himself into the world” within the flow of time.

Instead of the grandeur or wonder it offers, what makes Éric Poitevin’s photography so moving is its ability to readjust the relationship between viewing and the world. Within the tranquility of his images, viewers relearn how to pause, feel, think, and breathe. When confronting his works, viewers encounter not only the things photographed, but also their states of being within time. At the same time, these images are never merely flat representations: the plants carry a painterly atmosphere of stillness; the bodily vocabulary of birds, deer, and skulls forms sculptural arrangements through stretching, suspending, and placement; and the forests draw the gaze inward through the extension of lines and the breath of details. This ambiguity that crosses the boundaries of painting, sculpture, and photography allows all things to be measured by time in their own manner, while photography simply serves as the means of capturing such measurements. The “mastery of time” addressed in TÁR is given a different interpretation here: time is neither frozen nor dominated, but gently guided, leading viewers gradually toward the true destination of the image—a posture that allows viewers to walk alongside time, recalibrate their breath, adjust their rhythm, and rediscover the world.

Untitled|Giclee|48 × 60 cm. (Image) 50 × 62 × 4 cm. (Frame)|2010|Ed.5. Untitled|Giclee|110 × 88 cm. (Image) 112 × 90 × 4 cm. (Frame)|2014|Ed.5.

[1] Blossfeldt, Karl. UrformenderKunst(ArtFormsinthePlantWorld). 1935. illustrate rated book, containing 96 photogravures. 318x248 mm.

[2] You think you photograph a scene (scène) because you enjoy it—in fact, it is the scene itself that desires to be photographed. You simply play the role of an extra in the staging of the scene itself (sa mise en scène). The subject is but a proxy for the ironic emergence of things themselves. Lin, Chi-Ming, Multiple & Tension: On History of Photography and Photographic Portrait. Taipei: Garden City Publishers, 2013. p. 216.

[3] Mayeur, Catherine, and Jean-Charles Vergne. EricPoitevin:Photographies,1981–2014.Paris: Toluca, 2014. p.9.

[4] C’est une sorte d’illusion, d'entre-deux, que je souhaitais photographier.

[5] Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Translated by Richard Howard. New York: Hill and Wang, 1981. p. 27.

[6] Heidegger, Martin. “Building, Dwelling, Thinking.” Poetry, Language, Thought. Translated by Albert Hofstadter, Harper & Row, 1971. p. 227.